As someone who’s spent years working in the worlds of both K-12 and Higher Education, I’ve witnessed a worrying trend that’s been brewing for over two decades amongst students in both K-12 and Higher Education. It’s a crisis that gnaws at the very foundation of learning and critical thinking: a reading crisis.

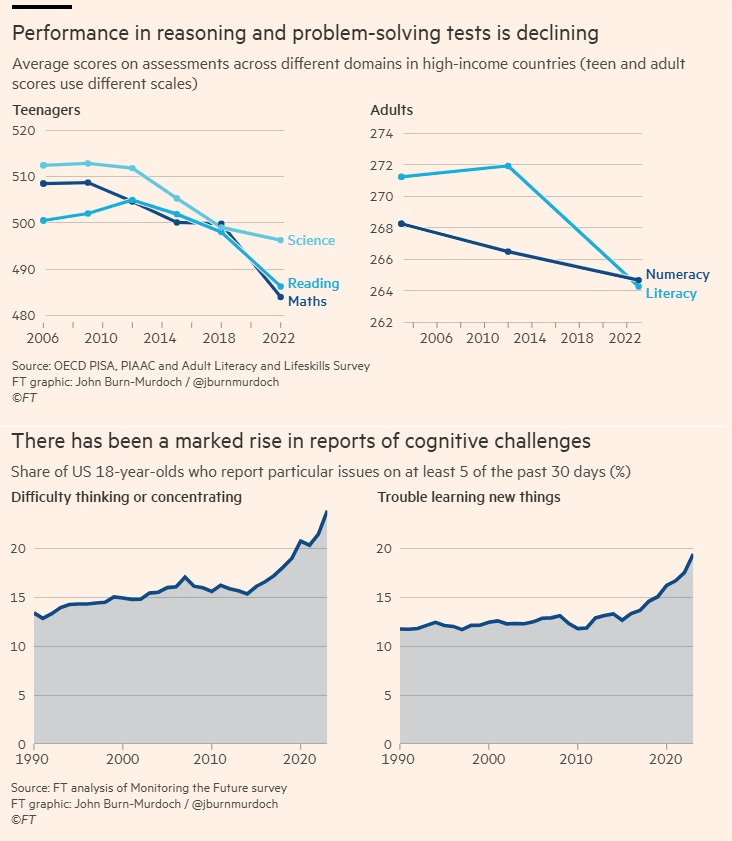

My concerns were recently amplified after stumbling upon a thought-provoking piece on “The Average College Student Today” on Substack and an equally unsettling article in the Financial Times by John Burn-Murdoch titled, “Have humans passed peak brain power?” These readings, coupled with studies highlighting a cross-generational dip literacy, problem solving, and reasoning, and my own anecdotal experiences working with students over the past decade, have led me to a stark conclusion: we are potentially facing an existential crisis, one that demands our immediate and collective attention. This isn’t just an educational and learning issue; it’s a societal one that needs to be addressed within our schools and beyond.

The simple truth is, reading isn’t happening on the scale it once did. This isn’t just about preference; it’s a significant problem. Reading serves as a cornerstone for knowledge acquisition across all disciplines and life stages. Without consistent and comprehensive reading, we are collectively losing the ability to acquire crucial contextual and content knowledge, which, as research clearly demonstrates, is foundational for deep understanding. This knowledge is the bedrock for synthesizing information and delving deeply into complex topics. This is something I believe is missing when I am working with students of all ages.

Think about it – academic studies consistently show a positive relationship between the amount of reading and the depth of understanding across subjects and age groups (Oliveriera & Santos, 2006; Fillippetti & Lopez, 2016). This foundational link is essential. Remember that seminal study that illustrated how students with limited general reading skills but extensive knowledge of baseball understood a baseball-related text better than proficient readers who knew little about the sport (Zhu, 2003)? This highlights the power of prior knowledge in comprehension. Individuals comprehend new information more effectively when they possess a foundational understanding of the topic at hand.

And it’s not just about understanding individual facts. The process of reading itself facilitates the development of interconnected knowledge structures. When we read about something we already know a little about, our learning of new vocabulary related to that topic accelerates. It’s a compounding effect where existing knowledge acts as an anchor for new information, leading to a more robust and nuanced understanding. The idea of using “text sets” – related texts focusing on a single theme for an extended period – can further deepen comprehension and solidify knowledge.

While the exact cause-and-effect relationship between general knowledge and reading skills is still being explored, the evidence strongly suggests a reciprocal connection: reading expands knowledge, and existing knowledge amplifies our capacity to learn even more through reading.

The Global Picture

Now, let’s look at the bigger picture. Globally, significant strides have been made in improving literacy rates over the past few decades. UNESCO data indicates that over 86% of the world’s population now possesses basic reading and writing skills (UNESCO, 2023). That’s real progress. However, despite this, hundreds of millions of adults still lack fundamental literacy skills, and a significant number of children aren’t acquiring even basic reading skills, hindering their future. The disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have only made this worse, potentially reversing some of the gains we’ve made (UNESCO, 2023). Data from the World Bank on “learning poverty” paints a concerning picture: a significant percentage of children in low- and middle-income countries cannot read and understand a simple story by the end of primary school (World Bank, n.d.). This global learning crisis extends beyond just getting kids into school. The Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) even revealed a decline in average reading achievement in many participating countries between 2016 and 2021, a period heavily impacted by the pandemic (PIRLS, 2021).

In the United States

Zooming in on our own backyard, the situation in the United States is alarming. The most recent NAEP reading assessment in 2024 revealed a continued decline in reading scores for both 4th and 8th grade students compared to 2022 and 2019 (NAEP, 2024). Fewer than a third of our students nationwide are performing at or above the NAEP Proficient level (NAEP, 2024). Think about that – a struggle to consistently understand and interpret written text for the vast majority. Even more concerning is that a significant proportion of students – around 40% of 4th graders and one-third of 8th graders – are performing below the NAEP Basic level (NAEP, 2024), suggesting difficulties with fundamental reading skills. This is the largest percentage of 8th graders scoring below basic ever recorded by NAEP and the largest for 4th graders since 2002 (NAEP, 2024). And it gets worse: the 2024 NAEP data also indicates a widening gap between the highest- and lowest-performing students (NAEP, 2024), with those already struggling falling further behind. When you compare the 2024 results to earlier assessments, the average reading score for 4th graders isn’t significantly different from 1992, while 8th grade scores show a clear downward trend over the past decade (NAEP, 2024). Even the NAEP Long-Term Trend assessment for 13-year-olds reveals declines compared to 2020 and a decade ago (NAEP, 2024). While the US scored above the OECD average in reading on the 2022 PISA, these consistent declines in NAEP data raise serious concerns about our future standing (OECD, 2022).

A Steady Decline

Why this decline? In our hyper-connected world, the answer seems increasingly clear: relentless distractions. The omnipresence of smartphones and the addictive allure of social media bear a significant part of the responsibility. Even when I was in high school in the late 2000’s these trends were beginning to emerge. With this said, it’s encouraging to see schools starting to react to this over the past couple of years, with initiatives like cell phone bans showing promising initial results. I even remember writing a blog post on this very topic, which resonated with many. Looking back to when I started in education in the mid-2010s, I clearly saw this erosion of reading requirements happening in the late 2000s and moving into my first years of teaching. The more recent movement towards the “science of reading,” which emphasizes systematic and explicit phonics instruction, reflects a recognition of the importance of foundational decoding skills. Despite this shift, the continued decline in NAEP scores suggests that the implementation of these new approaches faces challenges. Research indicates that reading on digital devices might not yield the same comprehension benefits as reading traditional print, especially for younger learners. Socioeconomic status also exerts a profound influence on reading achievement . Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting disruptions likely contributed to the recent declines in reading scores.

Our schools, and perhaps society as a whole, have seemingly drifted away from a strong emphasis on foundational content knowledge. True understanding necessitates retention, and reading, especially reading well, is instrumental in this process. Furthermore, the act of being assessed on what we read significantly reinforces that learning.

Now, let’s think about the types of materials we’re engaging with. Non-fiction literature is vital for directly imparting factual information and expanding our understanding across various subjects. It boosts our content-specific vocabulary and gives us the foundational knowledge needed for academic discussions in subjects like math, science, and history. It even fosters a researcher’s mindset by exposing us to facts, evidence, and different perspectives on real-world events. On the flip side, fiction plays an important role in stimulating critical thinking and broadening our cultural horizons. It allows us to step into the shoes of diverse characters, explore different settings, and experience events beyond our own lives. Literary fiction, in particular, has been shown to boost our social-cognitive abilities. It’s clear that a balanced approach incorporating both fiction and non-fiction is essential for well-rounded knowledge and skill development, yet non-fiction often gets less attention in reading instruction compared to fiction.

And we can’t ignore the disparities in reading levels. Within the United States, data from NAEP consistently reveals achievement gaps in reading proficiency across different racial and ethnic groups, with White and Asian students tending to outperform their Black, Hispanic, and Native American peers (NAEP, 2024). This points to systemic inequities in educational opportunities and outcomes that we must address. Gender also plays a role, with eighth-grade girls often scoring higher than boys in reading (NAEP, 2024). Furthermore, the correlation between socioeconomic status (SES) and reading proficiency is incredibly strong, both here and globally. Lower SES is consistently linked to reduced access to the resources that support literacy development, from books and quality early childhood education to well-resourced schools. This can create an intergenerational cycle of low literacy with significant consequences extending beyond academics into areas like employment, economic opportunity, and democracy itself.

Fixing the Problem

So, how do we begin to address this reading crisis? Here are a few of my thoughts I believe are critical steps forward. We need to act now on the following:

- Elevate Reading in Schools: We need a fundamental shift in our schools to prioritize reading at all levels. This means increasing the amount of reading required of students and increasing the rigor and frequency of assessments based on that reading.

- Phonics Instruction and Decoding from Elementary to Middle School: We need to focus on phonics and decoding longer than we have historically in schools. Beyond third grade, these are often not covered. To improve reading, we need to continue focusing on phonics and decoding as students age into Middle School.

- Implement Social Media Allotments: As a society, we must seriously consider implementing reasonable limitations on social media usage, particularly for those under the age of 18. Perhaps designated daily or weekly time limits.

- Reinforce In-Person Reading and Writing Assessments: While AI offers incredible potential, it thrives on a robust foundation of content knowledge. To ensure students are developing genuine comprehension and critical thinking skills through acquiring a vast library of knowledge, we need to maintain and strengthen in-person reading and writing assessments.

- Strategically Integrate Edtech in a Balanced Approach: Technology in the classroom is a valuable tool, but its use must be balanced. We need to create deliberate allotments that ensure students are developing essential skills both with and without technology, fostering true digital and AI literacy.

- Recognize the Power of Reading Beyond the Classroom: While research on traditional homework may be mixed, the evidence overwhelmingly supports the efficacy of independent reading. Encouraging and requiring reading outside of school hours is vital.

The reading crisis is real, and its implications are far-reaching. It demands a concerted effort from teachers, parents, policymakers, and society as a whole. We must reignite a passion for reading and recognize its indispensable role in fostering informed, critical thinkers ready to navigate the complexities of our rapidly evolving world. Let’s work together to turn the tide and ensure that the next generation possesses the intellectual depth and understanding that only a strong foundation in reading can provide.

References

Douglas, K. M., & Albro, E. (2014). The Progress and Promise of the Reading for Understanding Research Initiative. Educational Psychology Review, 26(3), 341–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10648-014-9278-Y

Filippetti, V. A., & López, M. B. (2016). Predictores de la Comprensión Lectora en Niños y Adolescentes: El papel de la Edad, el Sexo y las Funciones Ejecutivas / Predictors of Reading Comprehension in Children and Adolescents / Prognosticadores da Compreensão Leitora em Crianças e Adolescentes. Cuadernos de Neuropsicologia, 10(1). https://www.cnps.cl/index.php/cnps/article/download/219/232

National Assessment of Educational Progress. (2024). NAEP reading 2024. National Center for Education Statistics.

Oliveira, K. L., & Santos, A. A. A. dos. (2006). Compreensão de textos e desempenho acadêmico. 7(1), 19–27. http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1676-73142006000100004

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2022). PISA 2022 results: Volume I: The state of learning and equity in education. OECD Publishing.

Progress in International Reading Literacy Study. (2021). PIRLS 2021 international results. International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement.

Zhu, Y. (2003). The Influence of Background Knowledge on Reading Comprehension. Journal of Kunming University of Science and Teachnology.

2 thoughts on “The Reading Crisis: Where Are We At and Where Do We Go From Here?”