In my work with teachers, I’ve seen firsthand a significant challenge that has only accelerated in our tech-saturated world: the gap between how pre-service teachers use technology and their capacity to teach with it. This is the Consumer-to-Pedagogue Gap, and it is one of the most critical hurdles we must overcome in modern teacher preparation and on-going professional development and coaching as they progress forward in their careers.

This post outlines a framework to bridge this gap, moving teacher candidates from passive digital consumers to active, tech-enabled pedagogues. The central thesis is straightforward: we must replace passive observation with a system of structured, low-stakes rehearsal. This over time will improve instruction as well as the use of technology when integrated together.

This system is not built on intuition; it is grounded in established learning science, specifically the Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework and Cognitive Load Theory (CLT). These are the foundational lenses I advocate for in all effective instructional design (Rhoads & Lim, 2023).

The Pedagogical Imperative in a Tech-Saturated World

This “Consumer-to-Pedagogue Gap” is not a simple skills deficit. It’s a conceptual and experiential void. Before we can fill it, we must first diagnose its root causes.

Deconstructing the “Digital Native” Fallacy

A persistent myth that holds back teacher preparation is that of the “digital native” (Prensky, 2001). The idea is that because younger generations grew up immersed in technology, they are inherently equipped to use it for teaching.

My experience of coaching and leading 100s of new and seasoned teachers across K-20 education confirms what research has rigorously demonstrated: this assumption is false. As Kirschner and De Bruyckere (2017) highlighted, personal fluency with smartphones and social media does not translate to pedagogical competence. Using a tool for consumption is fundamentally different from leveraging it to achieve specific learning goals.

The problem is that the intricate pedagogical reasoning behind effective tech integration is often invisible to the student. Pre-service teachers have spent their K-12 careers as consumers of instruction, not designers. They experienced the front end of the tool (completing the task) not the back end (the educator’s complex design choices).

Our primary task in teacher preparation is to make this invisible design work visible and, more importantly, practicable. Failure to do so is the primary driver of the Consumer-to-Pedagogue gap.

The Foundational Lenses of Effective Tech Integration

To bridge this gap, we need diagnostic tools. In my work, I emphasize that we must move beyond focusing on the tool and instead focus on the learning. The two most powerful lenses for this are TPACK and Cognitive Load Theory (CLT).

TPACK as a Diagnostic Framework. The TPACK framework, developed by Mishra and Koehler (2006), builds on Shulman’s (1986) work to posit that effective tech-enabled teaching requires a synthesis of three knowledge domains: Technological (TK), Pedagogical (PK), and Content (CK). In my own work, I stress that true expertise, the digital pedagogue, operates at the intersection where all three are interwoven (Rhoads, McLaughlin, & Moore, 2022; Rhoads & Karge, 2025). A flashy app with no pedagogical purpose (high TK, low PK/CK) is just as ineffective as a content-rich lecture that misses a clear chance for technology to make an abstract concept concrete (high CK, low TK).

Managing Cognitive Load in the Digital Classroom

While TPACK describes what a teacher must know, Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), pioneered by John Sweller (1988), explains how the human brain learns. CLT is built on the premise that our working memory is extremely limited. As I stress in my writing on instructional design, the goal of any instruction, especially tech-integrated instruction, is to manage this finite load (Rhoads & Lim, 2023).

We must differentiate between:

- Intrinsic Load: The inherent difficulty of the content itself.

- Extraneous Load: The “bad” load generated by poor instructional design—a confusing interface, distracting animations, or unclear directions.

- Germane Load: The “good” load, which is the desirable mental effort required to process information and build schemas (Sweller et al., 1998).

In my view, these two frameworks are symbiotic. A teacher’s TPACK within a lesson is demonstrated by their ability to manage cognitive load. For instance, high TPACK is selecting a simple, an intuitive formative assessment EdTech tool (reducing extraneous load) to ask a thought-provoking question that requires deep application of a new concept (promoting germane load) (Rhoads & Lim, 2023). Our goal is to build our teachers TPACK skillset so they can design learning environments that honor our cognitive architecture.

The Rehearsal Spectrum: A Blueprint for Candidate Development

Knowing the theory is not enough. To bridge the gap, new and seasoned teachers must move from watching to doing. This requires a deliberate shift from faculty modeling (which can keep candidates as passive consumers) to rehearsal of pedagogy without and with the technology.

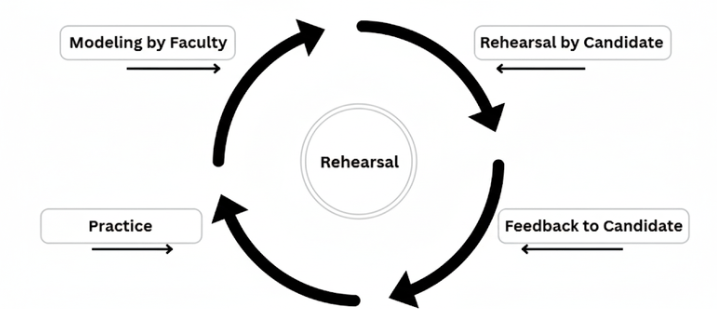

This form of training is grounded in practice-based teacher education (Ball & Forzani, 2009). In my work with coaching teachers, I’ve seen the power of “Modeling, Rehearsal, and Practice with Feedback” (Rhoads, 2025). This is not just practice; it is deliberate practice (Ericsson et al., 1993), which is structured, repeatable, and focused on improvement. The following protocols are a practical “rehearsal spectrum” to build this instructional fluency.

Protocol: Role Playing for Foundational Skills

Role-playing deconstructs the complex act of teaching into discrete, practicable skills. In small groups, candidates practice a specific move (like giving multi-step directions) while peers take on “student” or “observer” roles. This dramatically reduces the intrinsic cognitive load for the novice, allowing them to focus mental energy on mastering one component at a time before integrating it into a full lesson.

Protocol: Digital Speed Dating for Fluency and Feedback

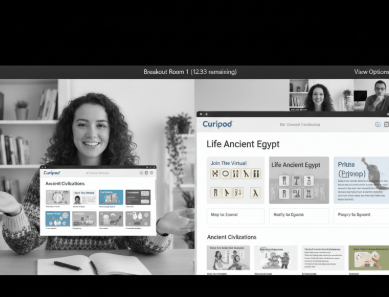

This protocol uses technology (video conferencing breakout rooms on Zoom or Google Meet) to facilitate rapid cycles of practice and peer feedback. After an instructor models a specific tech-integrated strategy, teachers are placed in small breakout rooms to rehearse it with peers. After a short cycle, the instructor automatically shuffles the rooms. This provides multiple “at-bats” for candidates to build TPACK fluency, synthesizing a tool (TK) with a strategy (PK) for a piece of content (CK) in a low-stakes environment.

Protocol: Station Rotation for Differentiated Practice

The Station Rotation model, a blended learning strategy I discuss in detail (Rhoads, 2022; Rhoads & Karge, 2025), is perfectly adapted for teacher preparation and on-going coaching and professional development. An instructor can create stations focused on different aspects of the challenge:

- Station 1 (Tech): Teachers practice the technical features of a new tool.

- Station 2 (Pedagogy): Teachers practice an instructional strategy (like Jigsaw) using analog materials.

- Station 3 (Integration): Teachers work on the most complex task: integrating the Jigsaw method with a digital tool.

This model is a direct application of CLT, allowing candidates to build requisite knowledge in isolation before attempting the more cognitively demanding task of integration.

Assessing for Mastery: Performance-Based Evaluation

Our assessments must mirror our practice. Instead of traditional exams (“Define the three types of cognitive load”), we must use performance-based, authentic assessments. The video journal assignment is an exemplary model. In this task, candidates create short videos demonstrating and analyzing EdTech tools, but with a critical component: they must explicitly evaluate the tools based on their impact on cognitive load and alignment with Universal Design for Learning (UDL).

This type of assessment, which I explore in my work on formative assessment and feedback (Rhoads, McLaughlin, & Moore, 2022), moves teachers beyond “knowing about” and into “thinking like” a pedagogical designer.

Cultivating the Ecosystem: Supporting Faculty and In-Service Mentors

Developing digital pedagogues cannot happen in a university vacuum when we focus this work with pre-service teachers. It requires a coherent ecosystem of support that aligns university faculty with their K-12 partners (Note: This also applies to instructional coaches and trainers in the K-12 arena).

The Faculty Community of Practice (CoP): A Model for Parallel Learning

To lead teachers through this rehearsal spectrum, faculty must engage in the same process themselves. A Faculty Community of Practice (CoP) provides a structure for this essential, parallel learning (Wenger, 1998). This model brings faculty together to address a shared “problem of practice” related to tech integration.

The CoP operates on the same cycle we expect from our students: identify a problem, learn a new strategy, rehearse it with each other, apply it in their own courses, and share the results. This parallel process is critical for authenticity. It ensures faculty are not just telling teachers how to be reflective practitioners but are actively modeling a career-long stance of collaborative, continuous improvement.

The Instructional Coaching Bridge: From Pre-Service Rehearsal to In-Service Refinement

The journey from consumer to pedagogue does not end at graduation. A seamless bridge must connect pre-service preparation with in-service induction. On-going instructional coaching is that bridge.

An extensive body of research confirms that high-quality coaching is one of the most powerful levers for improving teacher practice (Knight, 2007; Kraft et al., 2018). As I detail in 25 Tips for Instructional Coaches and Leaders, effective coaching cycles are built on this same foundation of rehearsal and feedback (Rhoads, 2025). The core components of coaching: co-planning, observation, rehearsal, and feedback—are the very same activities that define the rehearsal protocols used in pre-service preparation.

This alignment is the key: a preparation program built on rehearsal is systematically preparing new teacher candidates to be coachable (Rhoads, 2025). Novices who have spent years engaging in cycles of practice and feedback arrive in their first classroom with the habits of mind necessary to engage productively with a mentor. This “pre-induction” dramatically accelerates their growth and makes district induction programs more effective.

Matrix of Support Roles in a Rehearsal-Based System

A system built on rehearsal requires a shared language and a coordinated set of actions. The following matrix delineates the complementary roles of each adult in this integrated ecosystem

A Strategic Framework for System-Wide Implementation

These practices must move from isolated pockets of excellence to a coherent, system-wide strategy. This requires a strategic roadmap for both university and K-12 leaders.

Designing a Coherent Digital Pedagogy Pathway

Effectively moving new and seasoned teachers from consumers to pedagogues demands a programmatic sequence that embeds rehearsal across the entire preparation experience. A fully realized pathway would include:

- Accelerators (Workshops/Bootcamps): Foundational tech skills (TK) to ensure a baseline.

- Embedded Coursework: Rehearsal protocols (Role Playing, Station Rotation) integrated across all methods courses, building content-specific TPACK.

- Micro-credentials: Performance-based badges (like the video journal assessment) that require candidates to demonstrate their competence in applying theory to practice.

- Capstone Assessment: A culminating performance task where candidates plan, teach, and reflect on a technology-rich unit of instruction.

Leadership Levers for Sustainable Change

Implementing this framework at scale requires strategic leadership and a new, symbiotic partnership between universities and K-12 districts. The current system is often transactional; this rehearsal-based model necessitates a “new social contract” for teacher education, where both entities become co-owners of educator development.

This is a core component of building coherence and a collaborative culture, which I champion for instructional leaders (Rhoads, 2025). To enact this vision, leaders must pull specific, strategic levers:

For University Leaders:

- Invest in Faculty Development: Champion and fund the Community of Practice (CoP) model to provide faculty with the time and structure to refine their own tech-enabled teaching.

- Redesign Programmatic Requirements: Shift assessments away from traditional exams and toward performance-based rehearsals and portfolios.

- Forge Deep K-12 Partnerships: Move beyond transactional placements to co-design candidate experiences and co-train supervisors and cooperating teachers.

For K-12 Leaders:

- Invest in Instructional Coaching: Protect high-quality coaching as a core strategy for talent development and retention (Rhoads, 2025).

- Develop Mentor Capacity: Train cooperating teachers and mentors in the principles and protocols of rehearsal and feedback to create a common language for growth.

- Cultivate a Culture of Practice: Champion a school culture where collaboration, observation, and reflective practice are not add-ons but are central to the professional life of every educator (Rhoads, 2025).

References

Ball, D. L., & Forzani, F. M. (2009). The work of teaching and the challenge for teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(5), 497–511.

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406.

Kirschner, P. A., & De Bruyckere, P. (2017). The myths of the digital native and the multitasker. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67, 135-142.

Knight, J. (2007). Instructional coaching: A partnership approach to improving instruction. Corwin Press.

Kraft, M. A., Blazar, D., & Hogan, D. (2018). The effect of teacher coaching on instruction and achievement: A meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Review of Educational Research, 88(4), 547-588.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017-1054.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1–6.

Rhoads, M. (2022). Navigating the toggled term: A guide for K-12 classroom and school leaders.

Rhoads, M. (2025). Crush it from the start: 25 tips for instructional coaches and leaders. SchoolRubric Inc.

Rhoads, M., & Karge, B. D. (2025). Co-teaching evolved: Partnership strategies for an equitable, inclusive, & tech-powered classroom. Solution Tree Press.

Rhoads, M., & Lim, B. (Eds.). (2023). Amplify learning: A global collaborative – Amplifying instructional design. EduMatch®.

Rhoads, M., McLaughlin, J., & Moore, S. (2022). Instruction without boundaries: Enhance your teaching strategies with technology tools in any setting.

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4-14.

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12(2), 257-285.

Sweller, J., Van Merriënboer, J. J. G., & Paas, F. (1998). Cognitive architecture and instructional design. Educational Psychology Review, 10, 251–296.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.