Learning abstract concepts is difficult because our students are beginners in many cases. This means they primarily understand new ideas in the context of what they already know, which is usually concrete. To build a robust “schema” (a mental structure of organized knowledge), students need more than a definition; they need to see the concept in action. Cognitive scientists and practitioners often discuss the strategic use of examples and non-examples as an important facet of providing explicit instruction to ensure students understand the boundaries of a concept and do not overgeneralize rules (Ambrose et al., 2010; Groshell, 2024).

Furthermore, providing examples alone is insufficient. Without seeing what a concept is not, students risk overgeneralizing (thinking the concept applies where it doesn’t) or failing to distinguish deep structure from surface features. Therefore, we also need to provide non-examples as well.

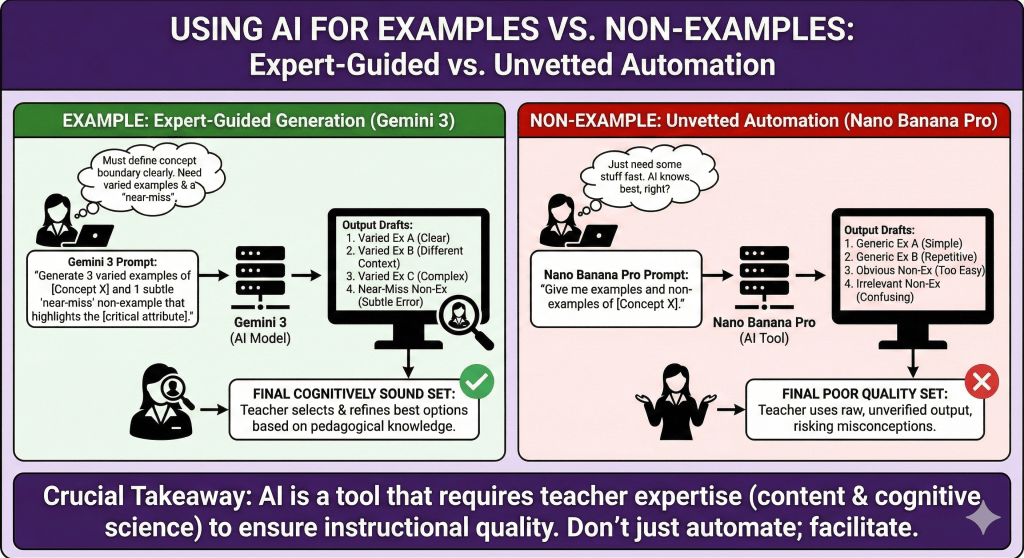

With this said, it is now ever been easier to create examples vs. non examples using Gemini’s Nano Banana Pro image generator that is associated with Gemini 3. It can create an infographic like example vs. non-example illustration as showcased below in several content areas. By selecting “Create Image” on Gemini 3 Thinking, you can use this tool by prompting it to create a example vs. non example by describing the concepts in detail and then within your prompt to develop in an infographic format that allows for a side by side comparison. Additionally in your prompt, discuss how your example vs. non-example should be structured to visually separate the concepts and use visual cues such as green and red text, cross outs and explicit error labeling.

Here are a few I created to start – I continue the discussion after these examples.

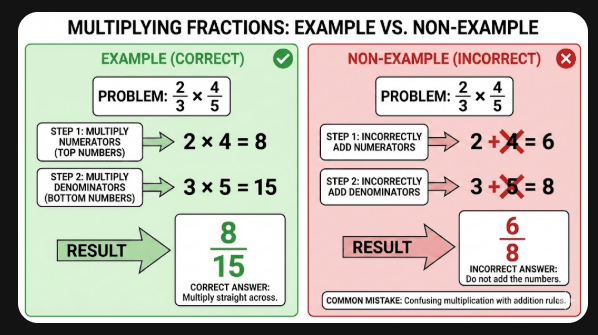

Example 1: Math

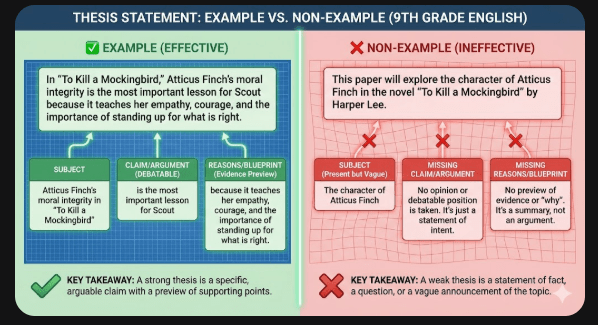

Example 2: Writing

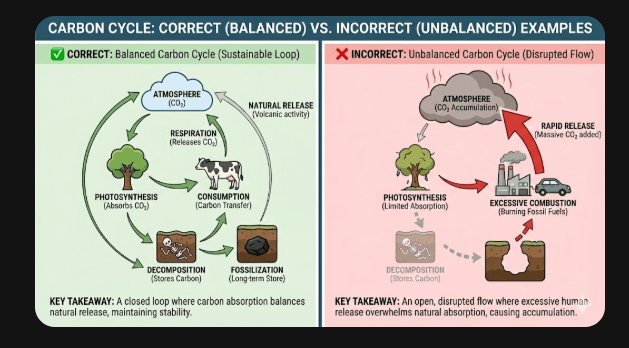

Example 3: Science:

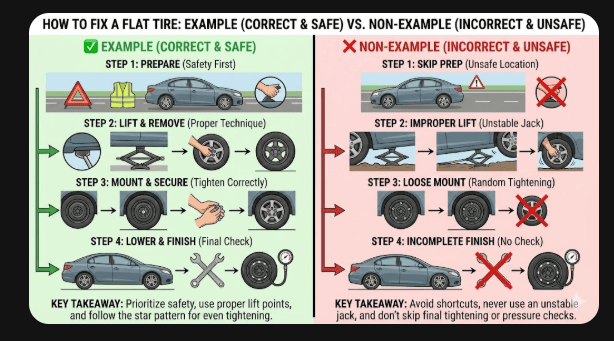

Example 4: CTE

Why Varied Examples vs. Non Examples are Critical

To ensure students develop robust mental models or schemas of abstract concepts, teachers must move beyond simple definitions and provide concrete illustrations through explicit instruction. Most important, this requires using varied examples rather than a single archetype. Presenting multiple examples that differ in their surface features is critical because it forces novices to identify the underlying “deep structure” of the concept instead of fixating on irrelevant details, thereby preventing under-generalization (Groshell, 2024; Surma et al., 2025). In contrast, varied examples only illuminate what a concept is; to fully define its boundaries, teachers must also provide non-examples. These non-examples act as the necessary “red light” to the examples’ “green light,” clarifying critical attributes by showing students exactly where the concept stops applying (Heal & Berlin, 2025).

Below, the goal below is to illustrate how this looks below with these two outputs related to multiplying fractions. For each of the following examples below, I describe what each is illustrating immediately after this set of images representing these examples vs. non examples as set.

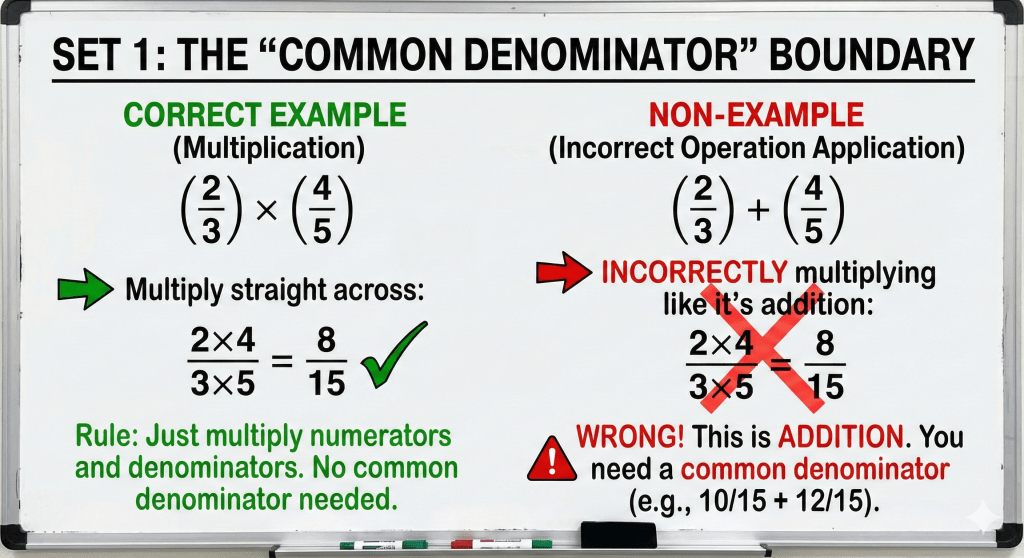

Set 1: The “Common Denominator” Boundary

The first example vs. non-example addresses the common error of overgeneralizing addition rules to multiplication. It visually contrasts the correct multiplication procedure with the incorrect application of the multiplication rule to an addition problem.

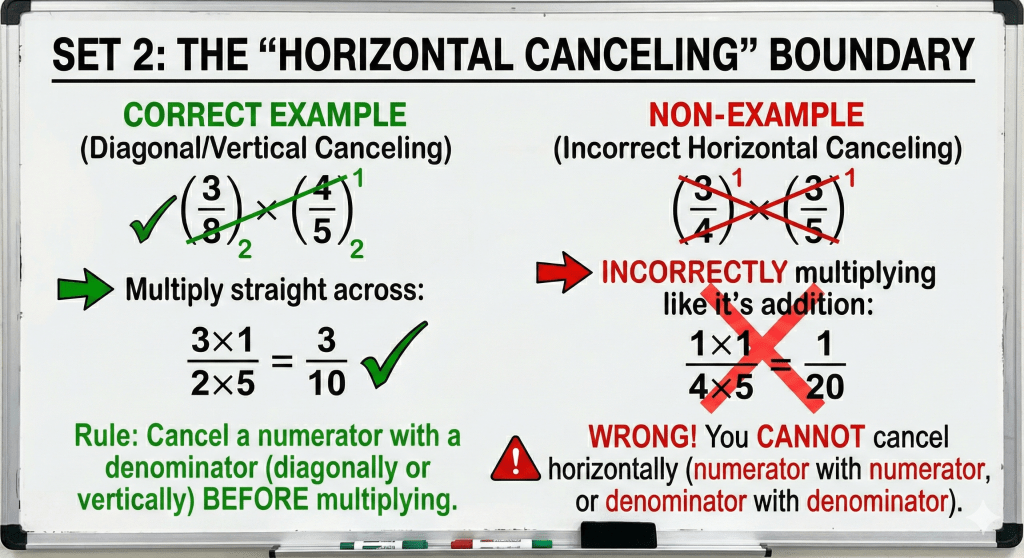

Set 2: The “Horizontal Canceling” Boundary

The second example vs. non-example focuses on the misconception that numbers can be canceled horizontally. It correctly shows diagonal canceling on the left and explicitly marks horizontal canceling as incorrect on the right, reinforcing the rule that canceling must be between a numerator and a denominator.

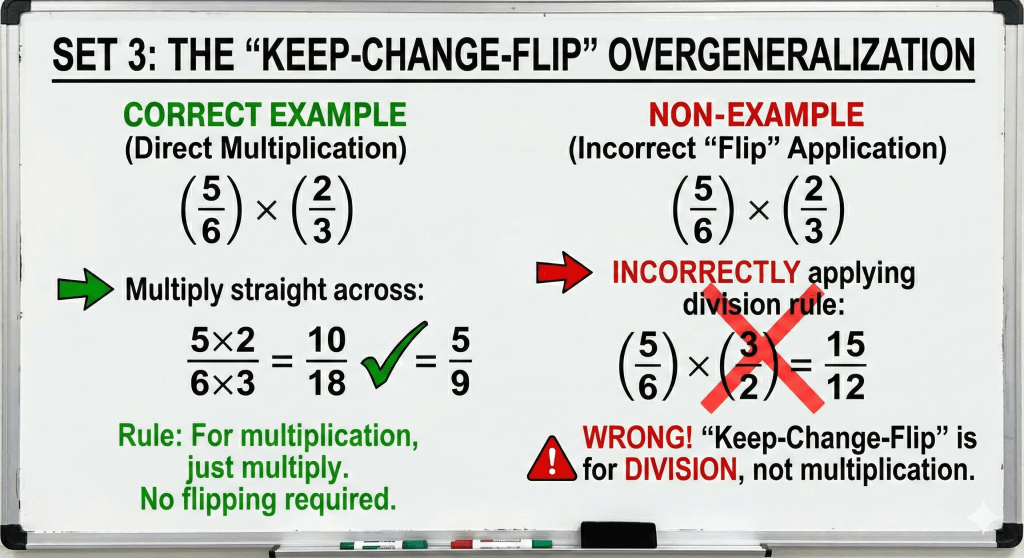

Set 3: The “Keep-Change-Flip” Overgeneralization

The third example vs. non- example targets the confusion between multiplication and division procedures. It contrasts a standard multiplication problem with a non-example where the student incorrectly applies the “flip” rule (reciprocal) that is used for division.

Moving Forward

The rapid advancement of generative AI models (like Gemini 3 and Nano Banana Pro) offers unprecedented opportunities to create rich instructional materials, such as varied examples and non-examples, even in real-time. However, while AI can accelerate production, it cannot replace pedagogy. The effectiveness of these tools rests entirely on a teachers ability to evaluate outputs through two critical lenses: deep domain content knowledge to ensure mathematical or factual accuracy (with this example), and a strong grasp of cognitive science to ensure instructional soundness. Teachers must know why a specific non-example is necessary to define a concept’s boundary to prompt the AI effectively and vet its generation. Without this foundation in evidence-based practice, we risk flooding classrooms with materials that are visually compelling but cognitively ineffective.

References

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. Jossey-Bass.

Groshell, Z. (2024). Just Tell Them: The Power of Explaining and Explicit Instruction. Hachette Learning.

Heal, J., & Berlin, R. (2025). Mental models: How understanding the mind can transform the way you work and learn. Hachette Learning.

McCrea, P. (2017). Memorable Teaching.

Surma, T., Vanhees, C., Wils, M., Nijlunsing, J., Crato, N., Hattie, J., Muijs, D., Rata, E., Wiliam, D., & Kirschner, P. A. (2025). Developing Curriculum for Deep Thinking: The Knowledge Revival. SpringerBriefs in Education.

Willingham, D. T. (2021). Why Don’t Students Like School? (2nd Edition).